Day-to-day sisu

Drawn to mathematics and art as a child, Katherine Longhurst saw architecture as the perfect intersection between the two. A partner in Sydney-based firm Perumal Pedavoli, she specialises in the design of correctional facilities. The Bimberi Youth Justice Centre, situated north of Canberra, demonstrates Katherine’s sensitive integration of colour, texture, light, sustainability and functionality – with a particular emphasis on locks!

Underpinning the synthesis of functionality and aesthetics, is a humane philosophy of rehabilitation, which infuses her work and has helped the firm establish a niche reputation in Australia and New Zealand.

Bimberi Youth Justice Centre

Katherine and I share a couple of things in common: we’ve both been to Jyväskylä in central Finland, the original home of famous Finnish architect, Alvar Aalto; and we both practise yoga.

While art still feeds Katherine’s imagination, the daily practice of architecture requires an attention to detail and the ability to manage multiple relationships in order the get the job done. It takes sisu, as Katherine describes in the following conversation.

Architecture as art?

Annie Talvé: You’ve got everything in your job, the creative and the detailed..

Katherine Longhurst: Yes, and I like that. When I’m talking through the concept design with a client, I say: “We may be talking about this now but in a few months’ time we’re going to be talking about door handles.” There are a lot of things to consider and if something goes wrong it’s always the architect’s fault! If it goes right, nobody mentions it.

AT: Philosopher, Elizabeth Grosz, describes architecture as the original art form. She says that the framing of space enables all other forms to emerge…..Is architecture an art?

KL: Some days, but it’s only a small component. The creative spark is what makes architecture special, but it is only a small percentage of the time you spend as an architect. Most of it is about technology and technique and build-ability. I suppose the art is in the act of interpreting how people want to use the building, what will be done in it, translating their requirements into a three dimensional solution. And that flows through everything you do, you’re always thinking about how it fits into the big picture. I think it is an unconscious process, it becomes a way of doing things.

“You have to draw on sisu to get through because the end result is worth it.” Katherine Longhurst

Inspiration

AT: What inspires you?

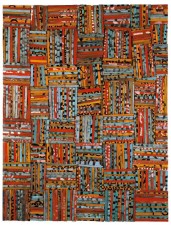

Rosalie Cascoigne: Jazz

KL: Inspiration is a hard thing to pin down. There are so many influences and ways of looking at things that help develop your perception of the world.

For example, when I first saw Rosalie Gascoigne’s retrospective in Sydney ten years ago, I floated out of that exhibition. I was inspired by the work. But you can’t then go and immediately translate that into architecture. What it does is make you think about proportion, materials and colour, and the idea of using things in unexpected ways.

My first overseas trip was to Italy. It was a great experience and when I got back I found myself designing all these Roman buildings, with courtyards and amphitheatres, big bold shapes. Louis Kahn and Alvar Aalto both had that reaction after studying in Italy. Aalto went back to Finland and started to design buildings with red bricks and terracotta imprinted on them, which hadn’t been seen in Finland before then.

AT: There is a geographical affinity between them, as Kahn was born in Estonia, but their architecture is different, don’t you think?

KL: Yes, but there is a strong geometric form they share and also their use of light.

AT: You must have been exposed to Aalto’s work when you studied architecture, but what happened for you when you went to Finland and to Jyväskylä in particular?

KL: Aalto’s buildings are really comfortable to be in, they have an accessible human quality to them. It’s about light and that indoor-outdoor connection, but it’s also about humility. The buildings, although beautiful in themselves, are not monumental, they’re not trying to make a statement. And I think that’s why they’re nice to be in because there is a sense that they are there for people and not just to be admired as a sculpture, which some architecture can be.

If you think about the kind of architecture Aalto was exposed to as a young person and what he would have studied at university, and then place that against the buildings he later designed – he was radical. Where did those ideas come from?

AT: Even when he set up Artek with his first wife, Aino, and started making those gorgeous objects, they weren’t meant to be just design objects, they were for people..

Alvar Aalto Museum

KL: Yes, they came from a functional requirement, a need to have furniture that was comfortable, that met a particular need for the people using a building and that was compatible with the building. They used materials respectfully and didn’t waste anything.

AT: I also admire the way Aalto was inspired by what was happening with Bauhaus design in Germany and adapted plywood to create his own shapes by working closely with the same manufacturer for his whole working life. He was able to invent new shapes and new uses for those shapes.

KL: That’s right, he didn’t just design, build it and that was it; it was a development process over many years. They refined their techniques to make things more accessible and easier to build. I actually visited the Korhonen furniture factory and they had placed some of the original Artek stools against the contemporary ones and were able to explain the differences.

Artworks by Aalto

AT: Like many creative people, Aalto was able to move between different genres. At the Aalto Museum you can see the full range of his chairs and also his paintings. Buildings, furniture, art – he was restless in his need for self expression. Are you like that?

KL: I sew, I’m a dressmaker. I make all of my own clothes, I find it very therapeutic. I don’t need any more clothes, I’ve got plenty, but I still keep going. I love the act of sewing. I remember when I was in Year 3 at school, we had a sewing teacher, Mrs Peters, who was very good at her job. Even the boys sewed things. My grandmother also taught me things and gave me my first sewing machine. Like anything, it takes time.

Read more of this interview: Project Sisu Sydney Winter 2009