Le Corbusier in Ahmedabad

Originally built in 1931 to commemorate the 70,000 Indian soldiers who lost their lives fighting for the British Army during World War I, India Gate in New Delhi soon came to symbolise the soaring hopes of the newly independent Indian nation after 1947. Post colonial India was determined to be modern. The Bauhaus feel and tone of Delhi’s wealthier residential suburbs have produced a vernacular style influencing the shape of the city today, including contemporary buildings like the excellent bloomrooms hotel in which I recently stayed.

Brand new cities like Chandigarh in Punjab and Gandhinagar in Gujarat were beneficiaries of the progressive zeal that infused the country, influencing the choice of architects invited to work on major public and private projects. It was India’s first PM Jawaharlal Nehru who personally commissioned the famous 20th century Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier (Charles Eduoard Jeanneret) to design the city of Chandigarh. Le Corbusier also left his mark on discrete building projects in other North Indian cities like Ahmedabad. A textile trading hub since 1411, Ahmedabad had 70 textile mills scattered across the city when Le Corbusier was approached to design a flagship building for the Mill Owners’ Association in the early 1950s. Built between 1952 and 1954, the building has served the Association well for nearly 60 years, although parts of it had fallen into disrepair by the 1990s.

“The materials of city planning are sky, space, trees, steel and cement in that order and in that hierarchy.” Le Corbusier

Concrete, steel and glass

Still a bustling commercial town, Ahmedabad is split in two by the Sabarmati River: the old town hosts a medieval tangle of havelis, free roaming cows and open air markets; while the new city across the river is bursting with shopping malls, educational facilities and large residential compounds owned by Gujarat’s recently returned, commercially successful NRIs (non-resident Indians).

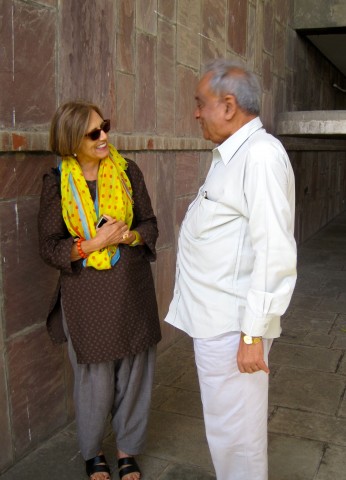

An Ahmedabad native, Mr Abhinava Shukla is the current Secretary-General of the Textile Mills’ Association, and on the day of our visit to the Mill Owner’s Building we were lucky to have him to ourselves. From the street, the tumbling foliage that spills out of multiple terraces on the building’s two lower levels, a distinct forerunner of the now popular vertical garden movement, softens the otherwise stark concrete facade. A ceremonial ramp leads up to the building’s entrance, where we enter via a huge crimson-red door into a concrete-cool triple-height interior that contains floating staircases and specially molded concrete benches offset by touches of colour like the red entrance door and its canary yellow companion. A building length wall in local river stone provides textual contrast to the sea of concrete, and speaks to the river Sabarmati that once lapped at the edges of the building’s landscaped gardens. The rooftop was designed to accommodate hydroponic agriculture that would also help cool the building in summer, an environmental feature well ahead of its time. The garlanded terraces protect the windows from direct sun and are of sufficient depth and height to encourage cross ventilation. Mr Shukla is particularly proud of the third floor top-lit auditorium, which was covered in six inches of dust when he first took over. He showed us the special peek-a-boo window Le Corbusier installed to allow late arriving patrons to view and hear the action until a break in proceedings allowed them to take a seat inside. A small but engaging exhibit has been established nearby which explains the genesis of the building and makes reference to the three other architectural projects Le Corbusier completed in Ahmedabad during the 1950s.

A lightness of being

Le Corbusier used relatively humble materials like concrete and brick in original ways. Sanskar Kendra, the city museum Le Corbusier also designed, shares this lightness of being. Although it has suffered from neglect in recent years, the attention to detail Le Corbusier was known for is still evident. Suspended on narrow stilts, its rectangular form floats in space. Like the best of the Mughal monuments we experienced in Delhi and Agra, both buildings by Le Corbusier embody what my colleague Sally Gray calls the architectonics of space – that ineffable quality of what it feels like to be in a space where every detail complements the whole and vice versa.

Red entrance door

Yellow door inside the building

Floating staircase

Foliage and eaves encourage ventilation

Mr Shukla with Annie Talvé

Small exhibition space at Mill Owner’s Building

Sanskar Kendra Gallery on stilts

Photographs: All images taken by Annie Talvé and Sally Gray except thumbnail of Le Corbusier, which comes from the Le Corbusier Foundation