Oh, Yoko

Yoko Ono turned 80 this year, but you wouldn’t know it. She’s a little stiff in the joints, and who knows what lies behind those dark sunglasses she wears, but Yoko Ono is as sprightly and unpredictable as ever. She bounced onto the stage of Sydney’s Opera House in November and proceeded to belt out a haunting reverb-enhanced performance piece composed of gasps, cries, and strangely melodic sounds that spiraled around the words “I wish”. Holding the microphone close to her mouth with both hands, Yoko still managed to contort her lithe 80-year-old body into a sensuous dance to the beat of her vocal gymnastics.

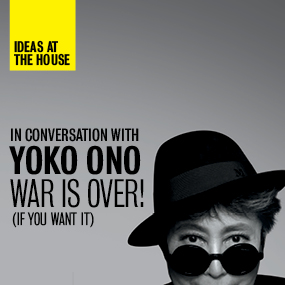

Yoko Ono in conversation at Sydney Opera House

It was the opening scene for an afternoon conversation between Yoko and the Museum of Contemporary Art’s Rachel Kent, who has curated a survey of Ono’s work called War is Over, If You Want It. Kent did a superb job of coaxing the soft spoken Ono to reflect on the song lines that run through her personal biography and rhizomatic (as Kent described it) creative output.

One of a kind

No matter what anyone thinks or says about Ono, there will never be another person like her. She is sui generis, one of a kind.

Born into a wealthy Japanese banking family in 1933, she lived a trans Atlantic life from an early age. Her father, an accomplished concert pianist, had to shelve his musical ambitions and enter the family banking business, moving constantly between Tokyo, San Francisco and New York before the outbreak of the second World War. Her mother was also musical, favouring Eastern music in contrast to her husband’s love of the Western classical tradition, and someone who shelved her own musical ambitions for the role of upper class Japanese wife and mother. They were both frustrated, Yoko said, and channelled their combined frustration into their eldest child’s early musical education. From the age of four, Yoko displayed a predilection for conceptual thought. Her mind veered towards what seemed impossible in the present but might be realised in the future. Her parents sent her to an avant-garde music school in Tokyo, where, as she fondly recounted, the students were asked to notate the sounds they heard around them – the chimes of a clock, the sound of trees swaying in the wind, the cacophony of the street. It turned out that Ono’s mother was a whizz with a super eight video camera, noted Kent, before we saw a short clip of a young Yoko dancing in a park with a jaunty hat on her head. It must have started then, quipped Yoko, her love of dancing and obsession with hats. Anyway, it all seemed fabulous – the off beat musical training, the constant movement between Japan and America, the privilege and unusually liberal outlook of her parents – then Japan entered the war. In New York at the time, Yoko remembered how the mood changed. It was a shock when the safety and love cascading around her, not just from her immediate family but the whole NY precinct in which they lived, was suddenly riven by racist propaganda. She was the Asian, and Asians were the enemy. Back to Japan they went, but it was hardly safe there. While the chronology of Yoko’s life at this time is a little vague, at some point Yoko’s mother sent the three Ono children to the north of Japan with a disabled maidservant (anyone who was fit and able was dragooned into the munitions factories that fuelled the war effort). It was there that she experienced her second major shock, not just privation but starvation. As the eldest child, now around 12, she also assumed a de facto parental role. Always hungry, swimming in uncertainty, Ono’s visual acuity was to be her saviour. It was then that she registered the sky: always there, always changing, always beautiful. It became her anchor, her “shiny thing”. “The sky never fails, it never betrays”, she told us, and it later become a constant motif in her work ( see image below).

The sky in a military helmet

Back in Tokyo after the war ended, another shock ensued. It had to do with money, previously a given in the Ono household. A new currency was introduced and the pre-war yen was now worthless. Yoko’s mother found this particularly tough. Such was the wealth of the Ono family that prior to the war her mother refused to touch bank notes that had been handled by another person. Each week she would receive a fresh bundle of newly minted notes, a practise which became unsustainable during and after the war. Changes to the privileged world the Ono’s had previously inhabited induced a shockwave from which her parents never fully recovered. Yoko meanwhile was coming to terms with her identity as an outsider: an outsider in America because she was Asian, female and eccentric; and an outsider now that she was back in Japan due to her cultural ambiguity. There was a term for Japanese who had lived in the West: they smelled of butter, it was said. So, smelling of butter, with a newly awakened visual sensibility, her training as a musician and pianist behind her, Yoko cemented her outsider status by becoming the first Japanese woman to study philosophy at Tokyo University.

Give peace a chance

Who knows how they all ended up back in New York, but it was there when Yoko told her father that she would never be good enough to be a concert pianist and that she wanted to study composition. It turned out, with the improbability that marks Ono’s entire life, that her father was a fan of the contemporary German composer Arnold Schoenberg. With her father’s encouragement she pursued avant-garde music, eventually becoming friends with John Cage, and setting up her own musical soirees in a Manhattan loft due to the paucity of venues available for emerging contemporary music. These were ultra-cool events: apart from Cage, Ono shared a few other famous guests with the Opera House audience, like Peggy Guggenheim and Marcel Duchamp. And, before the term performance artist even existed, she invented and performed some of the pieces she has reprised over her long career like Cut Piece, first performed in 1964. Feminist in intent, and typically thought provoking, video footage of Cut Piece/Peace shows a young, expressionless and motionless Ono on stage as people randomly emerge from the audience to cut pieces of cloth from her ensemble. Performed more recently in Europe, Ono told us that her friends wanted incognito security guards to join the audience in case things went too far, an offer she refused. Even her son, Sean, was worried for her welfare.

Cut Piece, first performed in 1964

Subversive, original and prolific, Ono was the most famous unknown artist in the world during the 1960s. That was John Lennon’s assessment anyway, and it was her art show in London that attracted Lennon’s attention. “You don’t want to hear about that old story,” she said. A chorus of “yes, we do” answered her back. “Okay, from the horse’s mouth so to speak,” she replied. And we heard about that first meeting, which culminated in Lennon climbing a ladder to see the word ‘yes’ inscribed on the ceiling; a message that he interpreted as an invitation, Ono now wryly observes. The rest we think we know, but do we?

For so long Ono has been demonised, categorised, demeaned, ridiculed, and, of course, pitied as a consequence of Lennon’s tragic death. Fortunately, she’s lived long enough and become, in her own words, open enough for some of us to almost catch up with her, almost understand her dogged insistence on crafting a creative life on her own terms. Yoko Ono is someone who swims beyond the pool, which, as I articulated last year, is someone who shares these characteristics:

- thinking outside pre-existing categories

- seeking different pathways for creative expression, and often inventing new ones

- showing resilience over time – Sisu.

At the end of the performance/conversation, Ono and host Rachel Kent left the stage together, arm in arm, to look at the sky outside (somewhat stormy and grey on this particular Sunday afternoon). She received a standing ovation. After a minute or so, she was back with an alarm clock in her hands. “The performance will end when the alarm goes off,” she said as she placed the clock on the stage and skipped away. I felt as if I were in one of quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s cat experiments: Is the cat alive or dead? will the alarm go off or not? My friend and I didn’t wait to find out. I’m still wondering, which, of course, is presumably the whole point. As I walked out of the opera theatre I heard someone behind me say: “She’s a cheeky bugger, isn’t she?”

More on Yoko from ABC