Neuro-hype

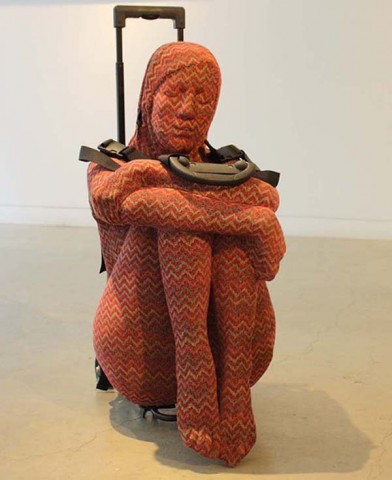

Pakistani artist Nusheen Saeed has created artworks depicting women as luggage. The cowered foetal forms Saeed renders as sculpture exude a disturbing eloquence. Malala Yousufzai and her school friends are gunned down in the streets of north-eastern Pakistan in 2012 for simply wanting an education.

Manal al-Sharif is imprisoned in Riyadh for daring to drive a car though its streets, even though it is not actually illegal. Australia’s first female prime minister, Julia Gillard (2010-13), is subjected to a torrent of shock-jock vitriol and verbal abuse during her turbulent three years in office. Biology is still destiny scream mullahs, clerics and rednecks. The ‘second sex’ is fixed and immutable they bleat, consigned by virtue of biology to be pack horses, public phantoms, and a lieutenant but never a general. This may seem a tangential way to start a discussion on neuroscience. But for all that contemporary neuroscience has given us – insights into learning, creativity, stress reduction and neural plasticity – the glib scientific materialism that underlies the hype of its most fervent promoters should be treated with caution, maybe even ridicule. Whether it’s the biology is destiny ruse, or the early 20 century racism enshrined in phrenology, scientific materialism has rarely served the interests of the oppressed.

One of Nusheen Saeed’s Baggage Women

More than our brains

Neuroscientist/philosopher Raymond Tallis calls it “neuro-mania”. While the neuroscience itself is a towering human achievement, he says, the exaggerated claims made on its behalf are in most cases dead wrong. The standalone brain says very little about us, argues Tallis, no matter how advanced fRMI machines become. Obviously, to be human you need a working brain, but it’s a mistake to think that this is all you need. “We’re more than our brains, we’re our bodies and our social environment. Human consciousness is inescapably relational.”

Neuro-psychiatrist/ literary scholar/ philosopher Iain McGilchrist says that dualities are misleading. There is consciousness and there is matter, and the perennial problem of how we understand reality: scientific materialism vs an elliptical world that is made up inside our heads. It is both, a two that is one, says McGilchrist, the yin and the yang. Like Tallis, McGilchrist argues that the brain is not a privileged part of truth, and that “if you think you are absolutely certain about something, you most certainly are not.” It’s just that when we move away from the comforting solidity science promises, things become more opaque, contextual and unpredictable. If a bridge exists between these worlds, it is most likely comprised of metaphor, humour and art, like Saeed’s baggage women who need no art critic to interpret their message.

Social amphibians

As usual, there’s money and notoriety to be made out of instrumental promises though. And it’s not this that I object to per se, after all I’m as guilty as any other consultant in presenting myself as a fixer, and as delighted as anyone else when science reveals answers to hitherto unsolved conundrums.

No, what I object to is the Darwinian race for neural supremacy; the reification of the brain into the privileged repository of human consciousness; the spurious hypothesis that brain training will have a causal impact on organisational effectiveness and social cohesion; and the current mantra that a ‘healthy brain’ is a bulwark against unhappiness, loneliness and ill health. What I object to is the absence of a poetics that can conjure a world in which compassion, imagination, generosity, patience and perseverance – the qualities that constitute our experience as ‘social animals’ – are as equally regarded as the electrical impulses in our brains.

By Nusheen Saeed

We are amphibians, McGilchrist says, and it’s our great gift as humans to be able to live in two worlds – the material world of science and the ethereal world of poetry – at the same time.

References

McGilchrist, I (2009) The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Modern World, Yale University Press, New York and London

McGilchrist, I (2011) Public Lecture at the National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 21 September