Tiny Utopias – Part 1

One hundred kilometres east of Seville, the regional capital of Andalusia in southern Spain, sits a small pueblo called Marinaleda. Surrounded by centuries-old feudal estates (latifundia) owned by the Spanish nobility, and the wreckage wrought by three decades of speculative capitalism, Marinaleda is a tiny utopia.

While youth unemployment in contemporary Spain soars to 55 per cent, and general unemployment bumps along at 36 per cent, in Marinaleda nearly everyone is gainfully employed.

The 1990s property boom, followed by its post GFC implosion, has seen hundreds of thousands of people lose their homes throughout Spain, with Andalusia particularly hard hit. In Marinaleda though, everyone has a secure home; everyone has access to high quality shared facilities; and everyone participates in community decision-making. Marinaleda’s 1200 hectare village cooperative, El Humoso, produces olive oil for domestic and overseas markets. A mechanised cannery turns communal crops of tomatoes, beans, broccoli and artichokes into profitable tinned products. Decisions about what crops to farm, how to reinvest profits, and how to administer the pueblo are made collectively, often through town hall-style meetings.

Marinaleda’s flag

The long march

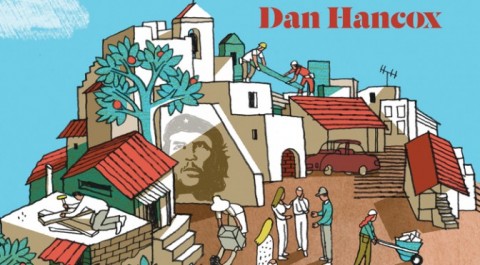

Thanks to British journalist Dan Hancox’s excellent book The Village Against The World, we learn how Marinaleda, once seen by bemused onlookers as an aberrant communist theme park, has become the subject of intense curiosity.

How have the village’s 2,700 residents resisted the global hegemony of neo liberal thought? How have the twin principles of mutual aid and collectivism trumped individualism and the profit motive? Is it a fake? That’s what Hancox sets out to investigate.

It turns out that the story of Marinaleda is intertwined with the eclectic philosophical outlook and ambitions of its mayor since 1979, Juan Manual Sánchez Gordillo. A true iconoclast, Gordillo has led a ‘ragtag army of boisterous upstarts’ out of abject regional poverty. Following General Franco’s death in 1975, for example, unemployment was a staggering 65 per cent. After three decades of political struggle, including hunger strikes and the illegal occupation of land (owned by the latifundia but largely uncultivated), the above mentioned 1200 hectares was carved out of the Duke of Intifado’s massive estate and ceded to Marinaleda in 1991. The crops chosen to be cultivated at the El Humoso farm are those that require the greatest amount of human labour, not the least.

Residents concede that none of this would have been possible without Gordillo’s vision and indefatigable leadership.

With his Che Guevara good looks and array of colourful bandanas, Gordillo cuts a striking figure. He has survived two assassination attempts and endless attacks on his character and motives. Hancox had reluctantly prepared himself to find an aging mini dictator, instead he found a charming and articulate champion of collective action and the power of a mixed economy. Marinaleda is in fact no Soviet-style kolkhoz (collective farm), it is comprised of cooperative ventures interspersed with small scale private businesses and private farm holdings. What differentiates it from everywhere else is its overarching collective spirit and enthusiastic capacity to mobilise solidarity – in the interests of its own population, and for workers’ rights across the region. Nobody believes that it is perfect, or that a utopia has been fully realised. Marinaleda is an ongoing experiment because, as Gordillo explains, “there is no future that is not built in the present.”

Juan Manual Sánchez Gordillo

Light on the hill

What can Marinaleda teach the rest us?

- It’s collective action that matters – consistent, dogged, purpose-led, and often inventive

- Even when Marinaleda’s citizens achieved their principal goals, they didn’t sit back and say, “I’m alright, Jack/Jill, too bad about you.” They are involved in ongoing campaigns to improve the rights of workers across Andalusia, and ardent defenders of the fundamental human right to dignified work

- Marinaleda asks us to imagine what it would be like if we used different frames to conceive ‘value’. What if full employment was our primary social goal? What if we judged success on the capacity of communities to make the tough decisions together? What if local communities could generate and allocate resources (like renewable energy) themselves, rather than relying on fork-tongued corporate entities who dance to the beat of a different drum?

At one point in The Village Against the World, Hancox allows himself to ask the obvious: “How do you go from a fevered dream, an aspirational blueprint, to concrete reality?“ Gordillo responds: “Utopias aren’t chimeras, they are the most noble dreams that people have. Dreams that through struggle can and must be turned into reality.”

It’s true that Marinaleda is not an ideal locale for IT consultants or merchant bankers; senior bureaucrats or architects. I’m not sure I would like to live there either. But when politicians and industry magnates trumpet the virtues of free market capitalism; peddle the so-called rationality of trickle down economics; privilege ‘efficiency’ over jobs; and deride the last vestiges of the ‘nanny state’ still extant; it’s good to be able to counter their self evident ‘truths’ with a living example. It’s good to know that there is something in between, a tiny utopia called Marinaleda.

The Village Against The World

References

Hancox, D. (2013) The Village Against The World, Verso, London

Hancox, D. (2013) ‘Spain’s Communist Model Village’, The Guardian Weekly, 8/11/13